As long as there is rice and Japanese pickles

I stand on the veranda outside Kuniko’s kitchen looking across the treetops towards the facing hillside. The viridescence of spring is deepening into a concentrated and uniform shade. Kuniko hovers in the doorway. The green is thickening, she says. Soon it will grow heavy, as opaque and oppressive as the heat.

She turns back into the kitchen to prepare tsukemono, Japanese pickles. I follow her in, the tile floor so much cooler against my bare feet than the sun baked concrete outside. She removes the lid and a white cloth covering her tokozuke pot and reaches a hand in. She has tended the same pickling pot for longer than I’ve known her. It is her comrade in the kitchen, a fermenting mixture of rice bran and konbu infused brine that must be mashed and turned and aerated daily. A healthy tokozuke is sweetly pungent, the aroma pleasantly sour and nutty. Its consistency light and airy as though foaming from within. Fua to suru, she says, her moist bran covered fingers extending from loose fists like a blossoming flower to illustrate.

For now the brown cylindrical ceramic pot sits on the kitchen counter but as temperatures rise she will move it into the cool pantry. A metal bowl nearby holds salted petit purple turnips, halved with their long wilting green locks attached. Another bowl holds a cucumber, half a carrot, and myoga, Japanese ginger. Kuniko had salted them couple of hours before and they glistened with sweat. She tucks them into the mealy bed and tamps down the surface until it’s smooth. Then she wipes the walls of the pot clean, covers it and sets it aside.

At dinnertime she’ll dig them up, wash the pickles and slice them. She ends each meal with these Japanese pickles, a bowl of sparkling white rice, and a cup of roasted tea. When the dishes are all put away, the kitchen clean and ready to sleep, she’ll pull the pot out one more time, add more salted vegetables, clean its walls, and put it away until morning.

Kuniko loves rice. She’s usually up and refilling her bowl for second helping before I’ve finished passing around cups of tea. But if she finds comfort in rice, she finds communion in tsukemono. A meal without rice and pickles just isn’t complete. Gohan to tsukemono ga areba, she says, as long as there is rice and pickles, by which she means whatever meal might come before matters much less.

In summer the markets fill with robust leafy greens and meaty vegetables. There is much to make of tokozuke, rice bran Japanese pickles. Cucumber, radish, new ginger, okra, myoga, and eggplant all relax in a bed of salty nuka, the bran polished away to render brown rice white. Lightly fermented they emerge simultaneously crunchy and pliant and soured in that way that good pickles are. A tokozuke pot brings elegant economy to the kitchen. It takes in the tips and tails and peels of vegetables from more glamorous dishes and returns them revised, tart and delicious and fit for the final course.

Years back Kuniko stood by my side as I made a tokozuke pot of my own. I mixed the bran and brine and seasoned it with slivered tougarashi for spice and broken bits of ago, small flying fish dried in the sun that give a burst of umami. I packed it into a black potbellied covered jar that Hanako gave me for the occasion. For two weeks I primed it with daily additions of sutezuke, salted vegetable scraps that are inevitably tossed, their purpose solely to inspirit fermentation and the development of flavor in the pot. I loved that tokozuke pot and everything it stood for, providence in the kitchen, flavor and grace at the table, a torch passed on, a tradition preserved.

But too often my diligence wavered and my poor tokozuke would moulder. Kuniko walked me through reviving it more than once. An exhausted tokozuke is deflated and limp and cries out for a shot of beer to rejuvenate fermentation. An overwrought tokozuke sends off a particularly acetic odor and is tempered with salt. My pot of Japanese pickles met its final end when I returned to the States. I was leaving for an extended spell and couldn’t find a caretaker. Those who are dedicated to the daily pickle have their own pot to tend. And those who aren’t just can’t be bothered. I emptied the pot, washed it clean, and flew away.

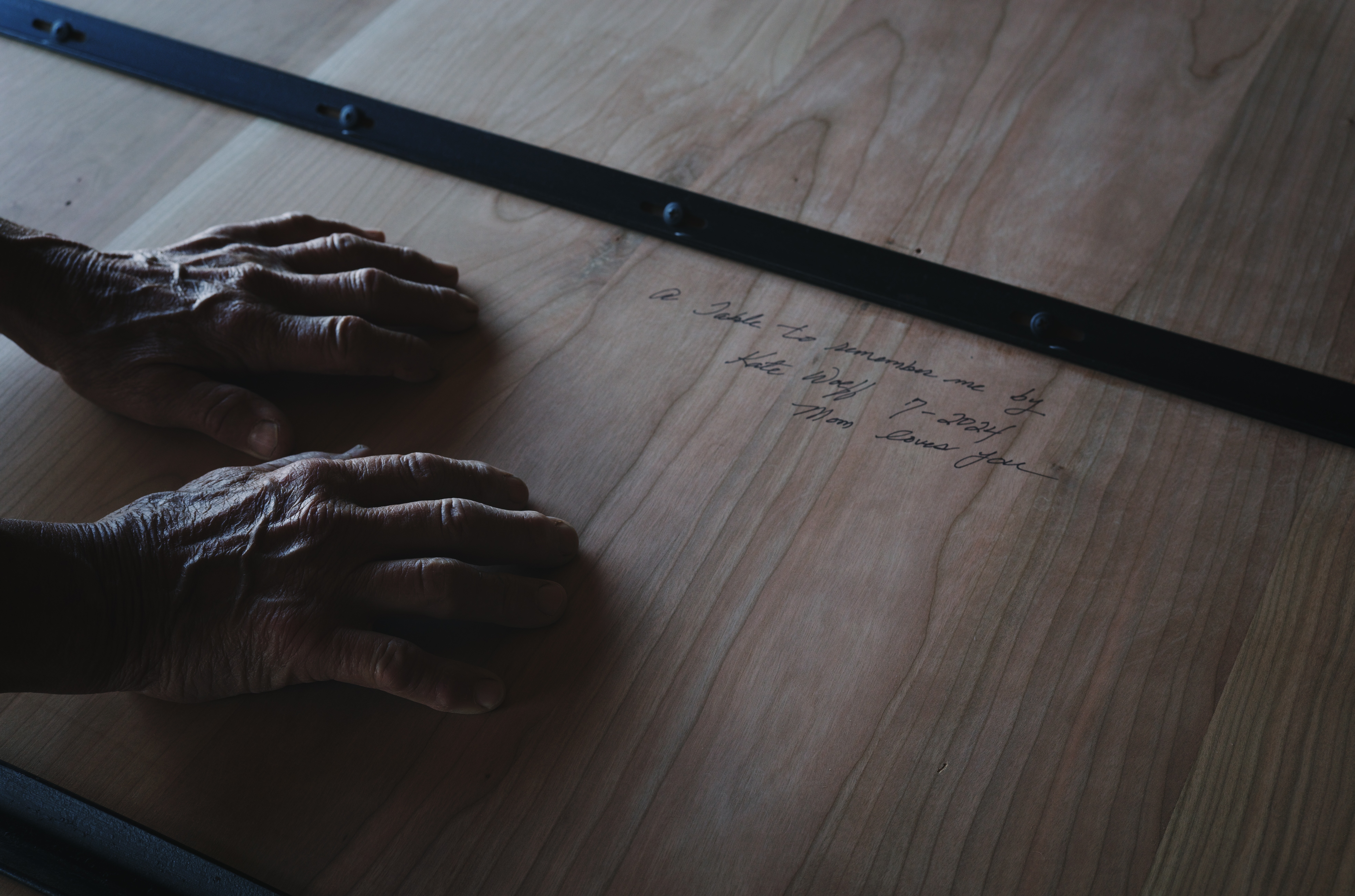

From thousands of miles away in Maine we learned that Kuniko lay in the hospital, unconscious and hovering on the edge of life. No one expected the stroke. Kuniko was 75, strong in body and stronger still in will and spirit. Before closing up the house, her eldest daughter Koo retrieved a ring as a keepsake and the tokozuke pot. She put it to work diligently in hopes of a day when she could return to her mohter. Kuniko would come home some months later, remarkably unaffected physically. But her mind found timing, order, and process less intuitive than they had been before. It was clear that her days at the helm in the kitchen cooking for us, her days as the culinary sun around which we all orbited, had ended.

Throughout these ensuing years Kuniko has never wanted for a good meal. All of her children, biological and married in, can cook. But the pull of the kitchen is strong and she has slowly found her way back into that most familiar room. There she is still in charge, if not of the meal itself, at least of the space. And though she leaves the most of the meal up to us, the tokozuke pot is still uniquely and entirely her own.

Japanese people say that each pot of pickles is flavored by the hand that stirs it. So it is no wonder that most favor the familiar taste of their own mother’s pickles. Though we miss her hand in the kitchen, Kuniko continues to nourish us through her soul food. On certain evenings when Koo has come to cook for her and Hanako and I sit down to dinner alone at our own table, we’ll hear a knock on the glass door. Outside Kuniko, breathless from climbing the hill, holds a bowl of tsukemono for us. One day I’ll tend a tokozuke pot again and I vow to be more diligent. But a single household needs only a single tokozuke pot. And hers really are the best, so as long as she is willing and able they are the ones we all prefer.