The birth of spring on the tongue

My memories of Mirukashi begin in this season, with the first foray to gather fukinoto just weeks after moving into our new house up the hill from Kuniko. I was so completely taken with the little green buds we found that day that I followed Kuniko into the kitchen and never left. It was a decisive moment, my ingress to the world of washoku. Japanese cuisine would captivate my heart and intellect and provide an entree into a new country, a new culture, and a new family.

In those early days we ate often with Hanako’s parent, Takashi and Kuniko. As afternoon turned towards evening, Kuniko would don her cream colored linen apron and start tidying the kitchen. Easing into initial preparations, she’d stand peering into her open refrigerator and slide a dozen glass jars around, examining the contents. That rough sound of glass on heavy-duty plastic still elicits a pavlovian anticipation of her cooking. She’d pull out a few things that might be useful, a nub of wasabi wrapped in a damp paper towel, a splash of leftover nikirishu, sake with the alcohol burned off, or a jar of dashi, fish stock in need of finishing up.

I’d stand at the wooden counter that separates her kitchen from dining room and watch closely as she set water to boil for blanching vegetables, then measured and rinsed rice in cold water, pouring off the milky white wash that carried away residual powders. When the water ran clear she’d set it in a strainer on the counter. The translucent grains slowly turned opaque at which point she was deep into slicing, sectioning, sautéing and simmering vegetables. As the clock neared six, my father-in-law Takashi would arrive. He’d clear an area near the sink, arrange his cutting board, knives, and cloths, and start preparing the day’s fish. He’d section bones for soup or grilling and slice the flesh for sashimi.

Takashi held court as the meal began, his guinomi of sake drained and refilled in quick succession. He was generous at the table, ensuring that all ate and drank well. If something was required he’d wave to his wife or daughter to get it. They might oblige once or twice but as the night wore on he’d more likely be rebuffed and sent into the kitchen himself. Hai hai, okay okay, he’d say getting up from his chair and shuffling, always bare-footed, into the kitchen.

Dinners were long, eaten over a course of hours. Inevitably a certain loneliness would settle in as those around me, growing increasingly tipsy and gleeful, traded anecdotes and appeared to discuss a myriad of interesting topics in a tongue that meant nothing to my ears. I found solace in the food, in the deeply satisfying and soothing flavors. I took interest in their arrangement and studied the order in which they came to the table. Night after night I watched and ate and soon began to feel the rhythm of a meal in this household. Sashimi opened the meal and was followed by two or three vegetables dishes. There might be ohitashi, cooked vegetables soaked in dashi and seasoned with soy, sesame oil, and a dollop of spicy karashi mustard. There were blanched vegetables in creamy dressings like shira-ae made of tofu or goma-ae made of sesame paste, or miso-ae, made of miso. Root vegetables were shaved or julienned, sautéed with dashi and soy, and presented as kinpira. We’d eat the grilled bones and flesh of seasonal fish and sip sake all the way through. A hot bowl of soup would signal the close of the main meal. By this time we had all had surpassed the feeling of full but a meal wasn’t complete without a bowl of rice with tsukemono pickles and a cup of roasted tea. Betsubara! they’d exclaim, calling on the extra stomach that always has room for rice with which, it seems, all Japanese are born. After a second helping of white rice Kuniko would lean back, drop her arms by her side and with a broad smile sigh, tabesugita, kurushi, deeply satisfied by the discomfort of having eaten too much.

Kateiryouri is home cooking, uncomplicated fare that nourishes the family, and this is what Kuniko offered us night after night. The flavors were simple and comforting, dishes mostly made with unassuming local ingredients procured at the market. I would slowly come to understand that what I was seeing and learning through Kuniko’s kateiryouri was rather extraordinary and distinct from the daily meals in other homes. Her joy in eating informed her ways in the kitchen and she held equal and inseparable her regard for the act of cooking and the act of eating. Fried foods were most delicious when just fried and crisp, soups most delicious when hot, and all of this required precise timing and an immediacy of preparation more often found in restaurants. It required constant attention, which she gladly gave it, and she was often absent from the table. To this day Kuniko values temperature, scalding is best, as another of the primary tastes, a preference likely born of eating quickly before getting up to prepare the next course.

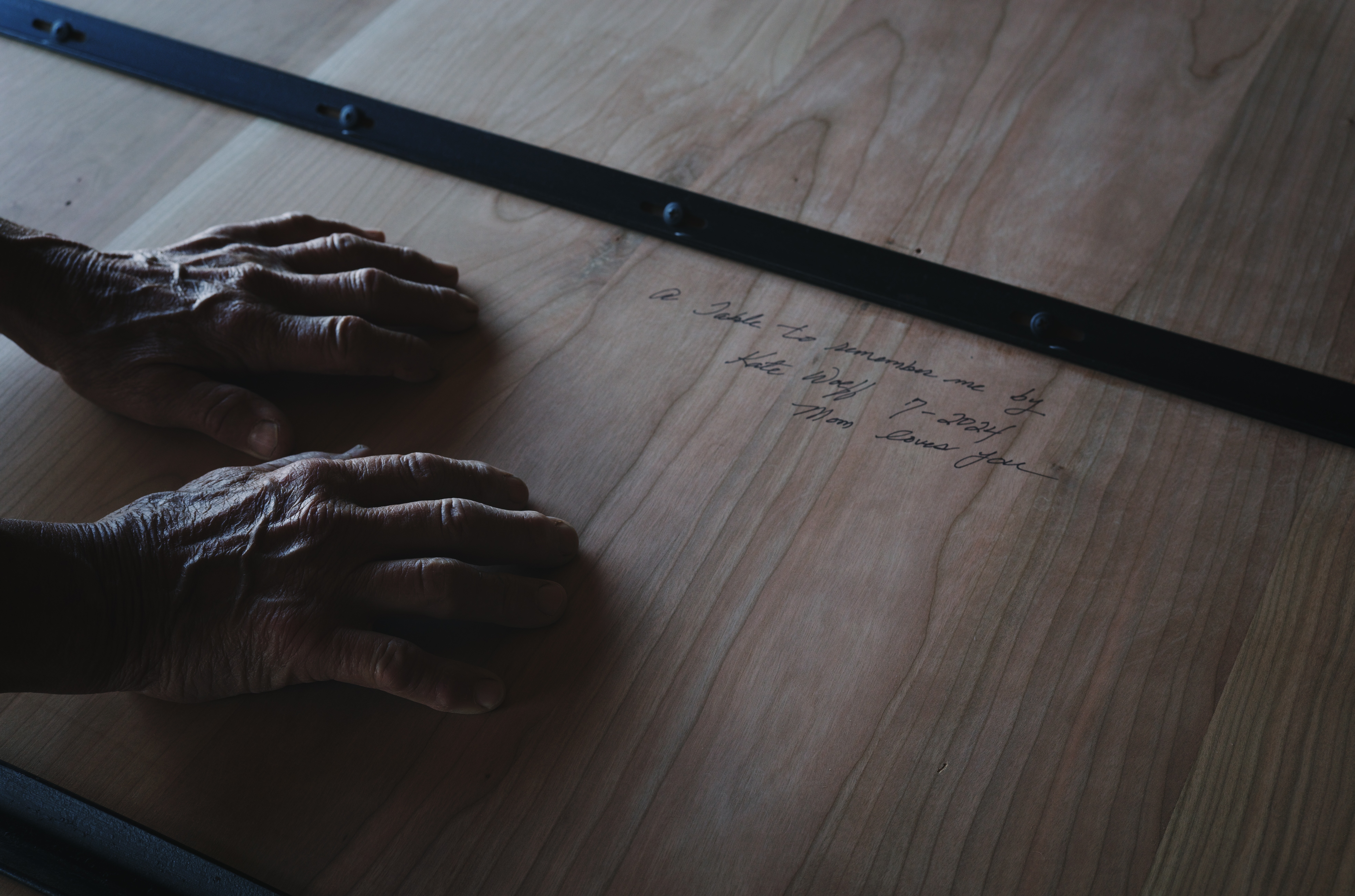

From the consideration of the cut and the preservation of color to the choice of vessel and the final arrangement, her actions were deliberate and measured. Her focus and attention made each dish shine through a myriad of small measures that elevated simple fare into elegant meals. I immediately found this everyday elegance, not to mention the flavors, captivating and still do. I soon longed to cook just as she did and hoped that one day I too could present a meal of honest, delicious food in elegant proportions as I saw her do night after night. As a wife and a mother of her generation, to feed her family and her guests was her duty but to do it as she did, with grace, beauty, and affection, that was her gift.

Roles have changed in the many ensuing years, and as her energy and interest in the kitchen wanes, I can now offer her meals like those she once made me. And with each passing year I take on more of the tasks on the annual culinary calendar like making umeboshi, tsukemono pickles, and now fukinoto tsukudani. I hope these flavors offers her a bit of solace hers once did for me.