Treasures of mountain and sea

There is fullness, a slowing down and settling in as spring gives way to summer. The frenzied pace of growth relaxes and days linger with us later. A keyhole through the black pines, mountain cherries, and angelica trees that grow behind the house allows a few piercing rays of the rising sun to shine directly onto my eyelids and I wake easier and earlier than before. We take long walks along a narrow road carpeted in pine needles that cuts through terraced rice fields. Newly flooded and planted, they reflect an image of clouds gridded by single blades of grass. In several months time, when the paddies are carpeted in green, each seedling will yield a hundred grains of rice. Along the marsh that borders the tangled mountain thicket beyond, clumps of wild yellow irises bloom and from somewhere deep inside the frogs sing their guttural song.

There is fullness, a slowing down and settling in as spring gives way to summer. The frenzied pace of growth relaxes and days linger with us later. A keyhole through the black pines, mountain cherries, and angelica trees that grow behind the house allows a few piercing rays of the rising sun to shine directly onto my eyelids and I wake easier and earlier than before. We take long walks along a narrow road carpeted in pine needles that cuts through terraced rice fields. Newly flooded and planted, they reflect an image of clouds gridded by single blades of grass. In several months time, when the paddies are carpeted in green, each seedling will yield a hundred grains of rice. Along the marsh that borders the tangled mountain thicket beyond, clumps of wild yellow irises bloom and from somewhere deep inside the frogs sing their guttural song.

One night Takashi walked in with a handful of fuki, the hollow stems of the native Japanese coltsfoot plant, in his hand. Hajimete, he said, this is the first time I’ve ever bought fuki. Only a hundred yen. The first time because fuki are a thing to gather, not purchase, but he really looked quite pleased with his 92 cent bundle. Fuki are umbrella like, each pale green stem with silver fur supports a single broad leaf with pronounced veins. Stems without a marked taper between root and leaf are preferred. Fuki are crisp and fragrant, reminiscent of celery, and ribbed with the same stringy fibers that must be peeled away for a more palatable bite. One sets a pot of water to boil before rinsing the long stalks and massaging them with a handful of salt by rolling the stalks back and forth on a cutting board. They rest while the water heats and began to sweat. Massaging with salt is a form of aku-nuki in which the bitter properties found in many wild vegetables, that tarnish taste and cloud the color, are removed. The salted and peeled stems simmer for a couple of minutes and sparkle a translucent shade of spring green.

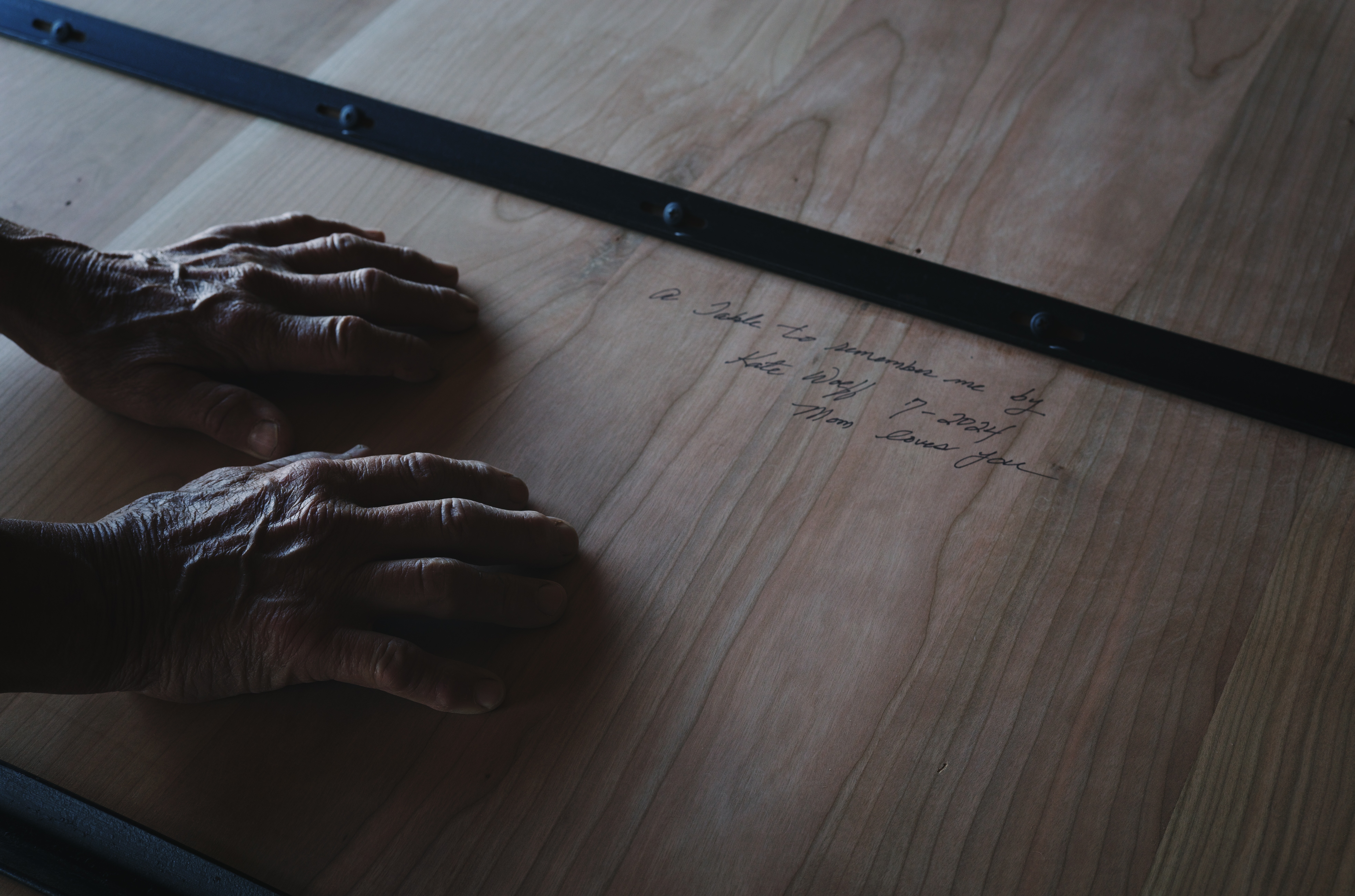

I think it was Takashi whom I first hear talk of the naturally complementing flavors of dishes that marry ingredients from the mountain to those of the sea. Over time I came to understand this principle as one of washoku’s many threads, that when followed from the table leads deep into the realm of culture and spirit. Japan’s native religion, Shintoism, still flows through the national psyche. Kami, the gods or sprits of Shinto, oversee the living landscape and the forces of nature, and their whims explain the shifting world to which early hunter-gatherer and later agrarian communities felt beholden. Rituals to honor planting and harvest, birth, marriage, and death, marked the cycles of a season, of a year, of a lifetime. Though less and less common in the ordinary household, these rituals often include an offering of food presented to the gods upon and altar, ingredients that are later used to prepare a meal to honor the day. It is said that in this meal the kami pass their energy through the food to those who eat. Alongside rice and sake, Japan’s most sacred food and drink, the kami are offered umi no sachi and yama no sachi, treasures of the sea and treasures of the mountains, two habitats that have fed the population for centuries.

Fuki are used in many ways, but in one I like best fresh asari, clams that are particularly delicious right now, are sautéed in a hot hollow pan. One by one they flip open releasing their briny juices. They are scooped out with a wire ladle and the blanched fuki then simmer in the remaining liquid. When the fuki are tender, the clams go back in for a quick mix alongside a few slices of ginger and a whole togarashi chili pepper before being arranged in a deep bowl. The clams provide enough salt to season the whole dish. In the last of the day’s glow, we pluck meat from shells while sipping sake and enjoy the sea soaked earthy flavor of fuki. Fuki close the curtain on sansai and the season of shoots draws to a close. For three months now we’ve traversed over hills, through fields, along streams, and into groves hunting and gathering an array of wild vegetables. They’ve reconnected us to the flow of time and the cycle of days. They’ve sharpened focus on the pattern of elements that feeds us through the conduit of new green growth. They’ve drawn us out and into the waking world and deposited us on summer’s doorstep fully in tune with a vibrant and maturing landscape.