Brining and pickling fresh new ginger

Walking into Kuniko’s pantry is like entering a laboratory. Under the bright glare of florescent lights shelves rise from floor to ceiling all around. They moan under the weight of bins and boxes and jars of every size containing edible specimens preserved in variously colored brines. There are a things in there that in my ten plus years here have never once appeared on the table. Whole heads of garlic float in syrupy soy aged from caramel brown to the intense inky black of a stick of sumi. In other jars, myoga bulbs are brined in rice vinegar, ume and sugar ferment into liquor, and the salt, oh the salt. An entire bin full of rare salts from around the world, some for bathing, some for seasoning, most received as gifts over the years and all squirreled away. Meanwhile she buys ordinary salt at the market. But the bulk of the shelf space is lined with eight liter jars stacked two deep of umeboshi, salted and dried ume plums made from the fruit of our trees each year. Each jar is labeled with its vintage, a range of dates reaching back more than ten years. Pickling and brining season is drawing near and when I stop by to return a few dishes to Kuniko, I see the door to her pantry open and harsh florescent light spilling out into the dark kitchen hallway. I find her inside, in the throes of cleaning and organizing to make space on the shelves for this year’s goods.

For many years Kuniko and Takashi have favored rice from a farmer named Eiji-san. He delivers ten-kilogram bags of brown rice to her door whenever she calls. This particular kindness is not uncommon in rural communities, a farmer stopping by with something you have or haven’t requested. When he delivers rice in early summer, Eigi-san always gifts a bag full of shin-shoga, his fresh new ginger. Kuniko saves out a few rhizomes to use fresh and opens brining season with the rest. The tan skin is so thin and smooth that there is no need to peel it away and the young flesh is crisp and fruit like without a hint of stringy fibers. The taste is light and clear, pronounced and gingery. She brines it in rice vinegar and salt. From time to time, when consolidations in the pantry turn up left over reserves of ume brine, she’ll add it in as well. The jar of ginger joins the large and extended family of jars in her pantry, right there, at arms reach. The shin-shoga floats in the dusty rose brine and over time the flesh takes on a pale pinkish hue, that same color of a fresh ginger tip where the rhizome meets the stem. Takashi might use a few thin slices of pickled ginger to garnish a plate of sashimi. Or we’ll slice it and eat it as tsukemono with rice at the end of a meal.

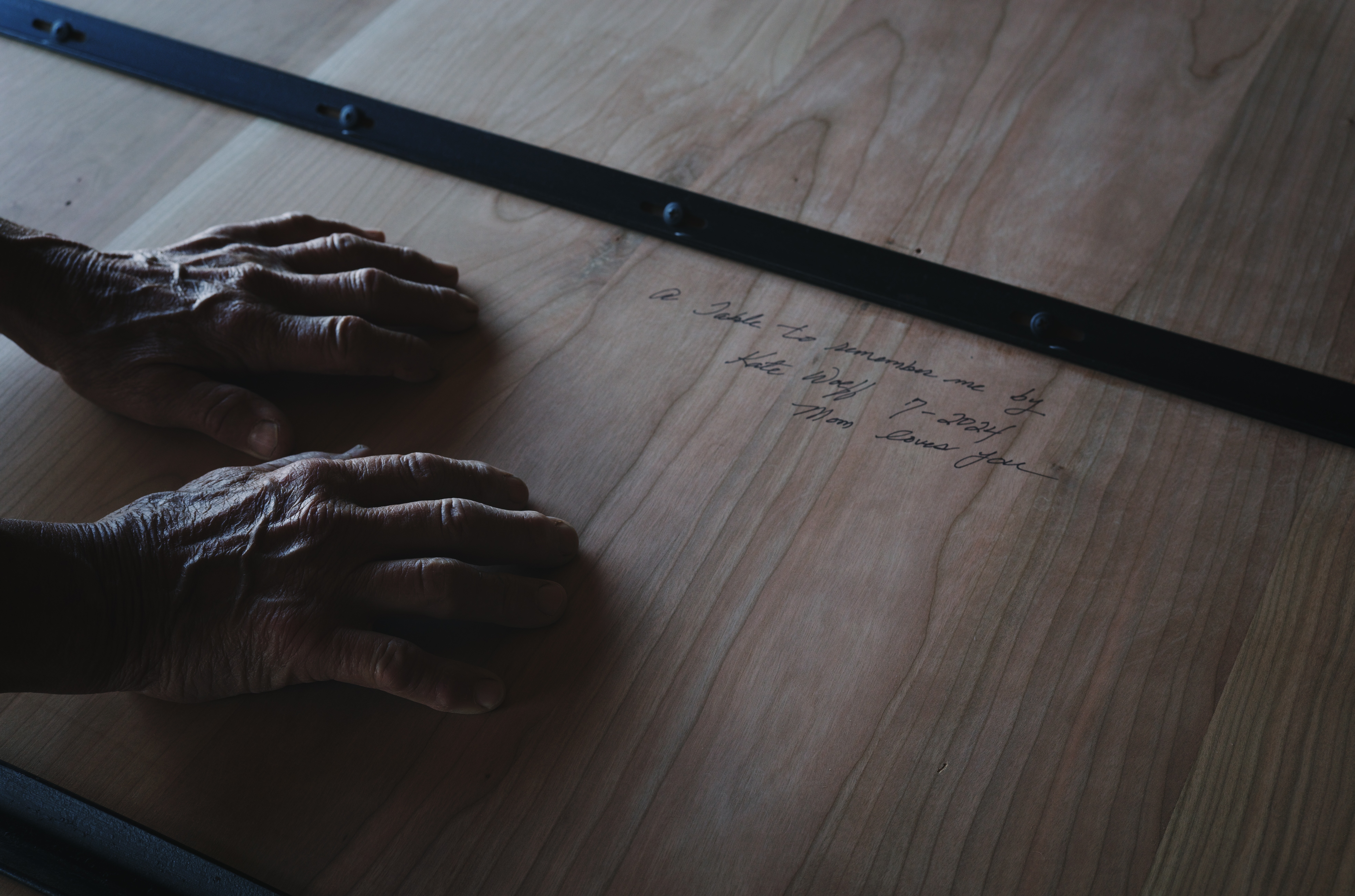

Kuniko collapses with a great exhale after a day spent retrieving and replacing heavy bins and jars from shelves up high, down low, and deep within the pantry, of standing at the counter brining ginger. Tsukareta. Honto ni tsukareta, she says, I’m tired, so tired. She slumps into a chair and rests her head on crossed arms at the table. A helper comes twice a week to clean and organize and do these physical things that need to be done but she prefers to govern the pantry herself. Even in her eighties she is as determined as ever in the domestic endeavors of cleaning, organizing, brining and pickling. These stores of food bring her comfort. When there is rice in the bin and water in the pot, when the larder is clean and full, only then can she rest easy.