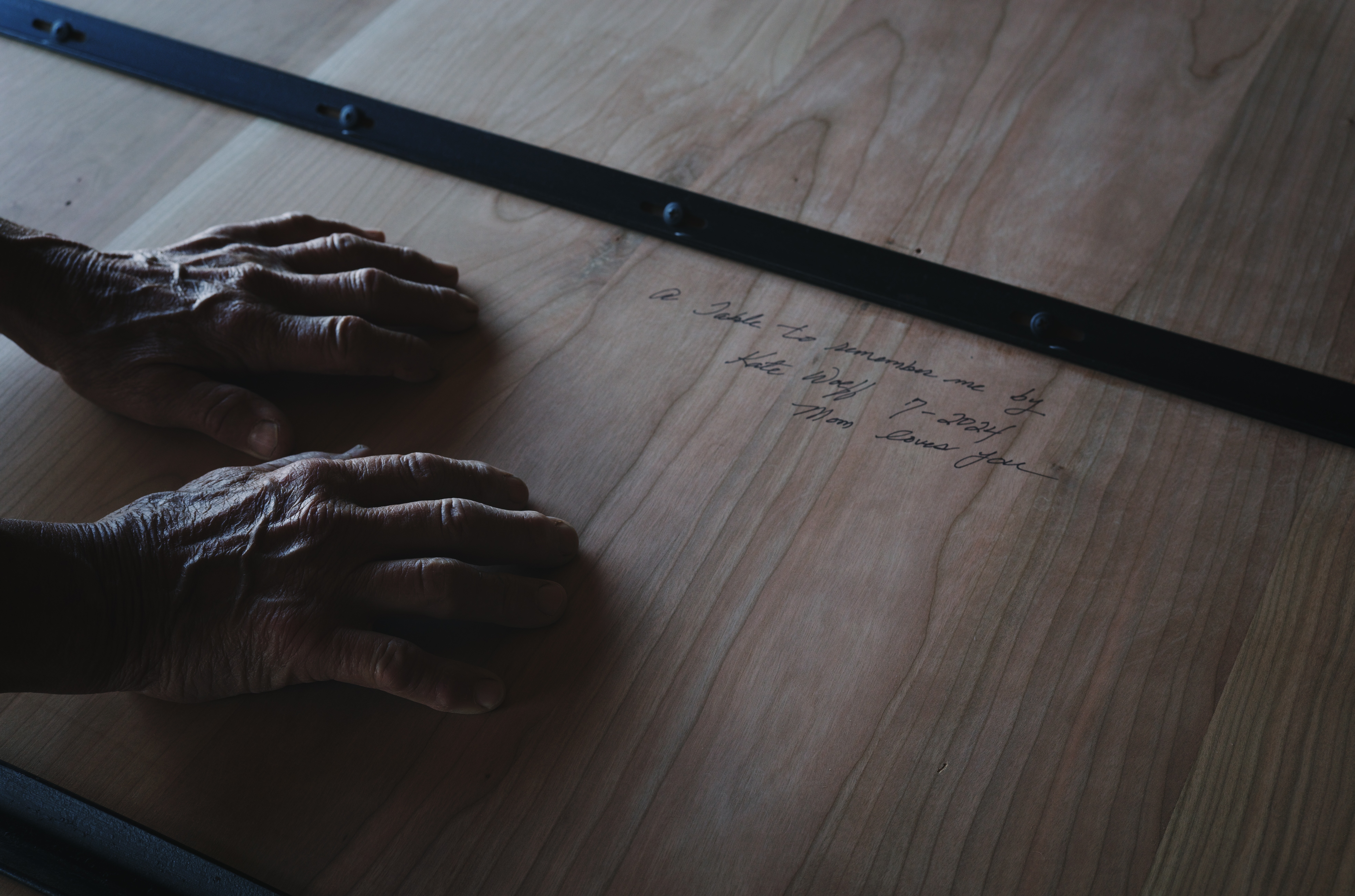

In the end, a new beginning

I immediately recognized in Kuniko the essence of the woman who nourished equally her guests, her family, and herself. Her meals brought such joy to everyone at the table, myself included, and I was eager to absorb everything she could offer. She represented a holy grail of cookery, a seemingly unobtainable well of information and ideas. At times it was almost maddening to see the deft with which she cruised around her kitchen making the most elegant fare from the most basic of ingredients. From dinner party to quick mid-week meal, at her home food was always served and consumed beautifully. It was simultaneously inspiring and intimidating.

Unfamiliar with the ingredients and the combination and ratio of seasonings, and with no fluency in the spoken language with which to seek clarity, I could become easily overwhelmed. Kuniko, a lifelong homemaker, had her own methods, measuring soy in capfuls, dashi by the spoonful, sake in splashes, and salt in pinches. This is in fact how all seasoned cooks work, but the beginner’s mind longs to formulate and measure and find a solid path to replication. I would watch keenly, scribbling copious notes detailing everything from amounts to sequence to her use of the knife upon a certain ingredient. I would steal into her quiet kitchen between meals to figure out how her capfuls and spoonfuls compared to standard measurements. Back in my own kitchen up the hill I would mimic her actions until I could replicate her dishes to exactness. Early on there was of course a good bit of floundering and confusion and meals that ended in a sense of defeat. When I lost my way, be it in technique or inspiration, I’d return to watch her again. My repertoire grew, albeit slowly. I could make a few seasonally significant dishes, then string them together into meals. But it might take all afternoon, or maybe even all day, and it would leave me both elated and exhausted.

As ten years in Mirukashi, then more, came and went, I grew into the kitchen. To replicate Kuniko’s dishes verbatim as I did for so many years was perfect training. It provided a foundation and familiarity in the world of kateryouri and brought the ingredients and seasons of Mirukashi into greater focus. Over time, I gradually felt no longer bound to learn one perfect dish at a time and what I had experienced for so long as the satisfaction of accomplishment or measurable improvement has evolved into the comfort of being present and relaxed and fully at home.

My years cooking with her also brought into focus the slice of washoku, Japanese cuisine, that I found most captivating, dishes that easily cross between kateryori, daily home cooking, and cha-kaiseki, the meal of tea ceremony. Dishes that are comfortable at the table on a weekday night but with a little extra care and attention could be elevated to ceremonial level. Kuniko’s dishes always pointed in that direction, restrained but elegant, seasonal and fresh. In the years since her stroke and her resulting absence from the kitchen, I’ve absorbed what I could through conversations with friends, books, experiences dining out, and most recently with expeditions into the world of fish with my father-in-law. But truth be told, I’ve longed to have a teacher again, someone to guide me, to introduce me to new ingredients, methods, and ideas.

If you had asked me with whom I would like to study, I would have named Tsuchiya san, the chef at a tiny place entered from an obscure Ginza alley in Tokyo. If I was lucky, I might eat there once a year, but the food astonished me every time. Courses flowed, like most restaurant of its caliber, along the lines of a kaiseki meal, the dishes handsome, the presentation elegant, void of any unnecessary flourish or decoration and rich with pure, clear flavors. Meals there exemplified the epitome of masterful cooking. With all thanks to the grace of fate and fortune, when he decided to close his restaurant and retire, he moved here to Karatsu, his wife’s hometown, and has agreed to teach me.

Last week I had my first lesson and in a single day we covered several extraordinary dishes, as much as I would have hoped to learn in a month. I learned to shave my own katsuobushi for dashi and we made sashimi of Olive Flounder. We cooked with ingredients I’d never encountered before, like dried zenmai, wild Asian Royal ferns, and itowarabi, made of the powdered root of bracken ferns. We deep fried ebi-imo, a variety of taro (pictured below), a dish I have long adored when served at Ginsushi. And made kaburamushi, a steamed dish of snapper, ginko nuts, and yurine the edible bulb of the lily plant, topped with the grated flesh of an enormous Kyoto turnip, served in dashi thickened with kudzu. It was simultaneously exhilarating and overwhelming. I was sent home with a bag of remarkable ingredients that are otherwise hard to find in Karatsu including high caliber wasabi, and kuwai, arrowhead bulbs (pictured above), each of which appears to have a map of the world drawn upon its skin. It took another long day to organize my notes but then I was off, determined to practice every dish before my next lesson. The kuwai chips won’t likely ever make it into a kaiseki meal, but I’m particularly keen to improve my tempura skills in anticipation of First Spring and the start of sansai foraging season, and they proved good practice. I dare say our dinners this year will be more delicious than ever. And oh, how I long to host guests again one day!